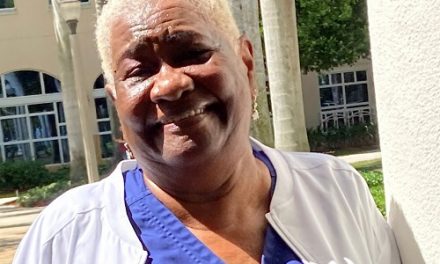

Kunjana Mavunda, M.D.

By Hilda S. Mitrani

Respiratory Syncytial Virus or RSV, as it’s commonly known, is wreaking havoc on one of our most fragile populations: babies. RSV season in South Florida is much longer than other areas, which means our infants and children are more at risk and for longer.

According to The Lancet, in 2019, 45,700 deaths in infants between 0 and six months were attributable to RSV. This year, health and medical authorities in the United States have sounded an alarm about the threats posed by the “tripledemic” of RSV, COVID and flu.

“Unfortunately, this year we’re seeing a surge of respiratory illnesses. This may be because of COVID-related isolation measures, during which the siblings and family members of many infants and children were not exposed to RSV or other respiratory viruses,” said Kunjana Mavunda, M.D., Board-certified pediatric pulmonologist at KIDZ Medical.

“The immune system of these infants and children did not recognize RSV when exposed, could not fight it, and thus the virus caused more severe symptoms. This is known as immunity debt,” Dr. Mavunda commented. “This season, we also have influenza, metapneumovirus and parainfluenza virus circulating at the same time. A child can get infected with more than one virus simultaneously – and this can lead to ICU beds overflowing in pediatric hospitals.”

For babies, young children, children with chronic medical problems, patients with immune problems, and the elderly, RSV may cause more severe symptoms and represent a serious threat.

“RSV attacks the respiratory mucosa,” commented Dr. Mavunda. “When the mucosal cells are damaged, the virus binds with these cells and other cells in the airway and produces syncytia, which are clumps of cells that occlude the airway. The cilia which brush debris and mucus out of the airway are also damaged.

“Newborn babies have more severe symptoms because their airways are small. When these syncytia occlude the smaller airways which the baby cannot use, they have to breathe fast and may experience coughing and wheezing. Then they may develop bronchiolitis or pneumonia. Because the cilia are also damaged, it is harder to remove these clumps of cells.”

Additionally, the baby’s immune system is still developing. Components of the immune system that are supposed to protect the airway may not be present.

According to Dr. Mavunda, “Airways of premature infants are even smaller than those of newborns. This puts them at a higher risk of complications when infected with RSV. Children with congenital airway problems, chronic lung disease, complicated heart disease, neurologic disease and some genetic disorders are also at much higher risk of developing complications after an RSV infection.”

RSV is easily transmissible. If a child in a daycare is infected, all other children will likely get the infection. Similarly, if a child brings the RSV home, all family members will get sick, although some may have minimal symptoms, from a runny nose to bronchitis, bronchiolitis, pneumonia and even death. Children at high-risk may need ICU admission and mechanical ventilation.

Unfortunately, after a severe RSV infection, the patient’s airway remains reactive, and they may have problems with recurrent wheezing. “If an infant gets another respiratory illness such as influenza, parainfluenza, metapneumovirus or even RSV again, the symptoms may be severe,” cautioned Dr. Mavunda. “When a patient needs hospitalization, it may take up to four weeks for the airway to become healthy again.”

For most people, RSV is just a cold with a runny nose, cough and/or sore throat. For babies and those at risk, the consequences can be devastating.

Dr. Mavunda was unequivocable about prevention. “I urge our community to continue its vigilance and follow preventive measures and prophylaxis wherever possible to ensure that our holiday season is full of joy and laughter, not hospital visits,” she concluded.