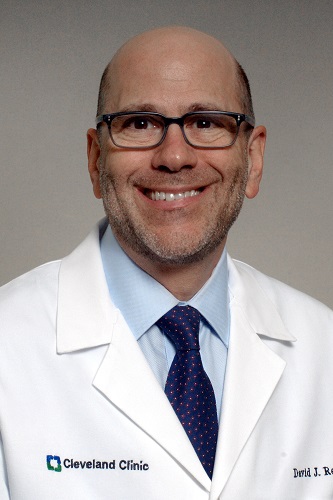

David J. Reich, M.D.,

A record-breaking 9,528 lifesaving liver transplants were performed in the United States in 2022. While laudable, transplant surgeon David J. Reich, M.D., never loses sight of the thousands who die while waiting for a transplant, who never achieve wait-list eligibility, and those who are removed from the list due to declining health.

“We’ve made great strides improving access to transplant care in recent years by expanding the donor pool, but many potentially viable organs are still going to waste,” says Dr. Reich, who recently joined Cleveland Clinic Florida’s Transplant Center as Surgical Director of the Liver Transplant Program and Chief of the Innovative Technology and Therapeutics Program. “That’s why machine perfusion is such a game-changer and has the potential to further expand the supply of donor organs.”

Dr. Reich is a pioneer in the modern use of donation after circulatory death (DCD) organ transplantation and has spent much of his career investigating innovative technologies for artificial liver support and organ preservation. He published one of the first successful series on DCD liver transplantation in 2000 and has shepherded widespread, international adoption of DCD over the past two decades.

Donation after circulatory death

Deceased organ donation is the main form of liver transplantation. While the majority are donation after brain death (DBD) organs, there is a growing trend in using DCD organs.

“Originally, all donor organs came from individuals who experienced cardiac or circulatory death,” explains Dr. Reich. “But in the 70s, this practice was abandoned in preference of organs from donors who experienced brain death because the organs do not suffer the effects of warm ischemic injury and are less prone to poor graft function.”

DCD organs experience lack of oxygen and damage due to anaerobic metabolism, as well as greater ischemia and reperfusion injury impacting organ recipients. “In particular, DCD livers result in higher rates of graft non-function and biliary complications, demonstrating the need for better preservation techniques,” notes Dr. Reich.

Organ preservation with machine perfusion

Static cold storage (SCS) has been used for decades with good outcomes to preserve and transport standard criteria donor (SCD) organs. It entails placing organs on ice with a preservation solution. This method, however, does not achieve ideal post-transplant results with DCD or other extended criteria donor (ECD) organs.

Recently, ECD organs are increasingly preserved with machine perfusion technologies to circulate oxygenated blood and fluids through the donor organs before transplantation. Normothermic devices just gained FDA approval and hypothermic devices have completed or are close to completing clinical trials in the United States.

“With machine perfusion, we are working to improve how we preserve organs from donors who are older or with comorbidities and from DCDs,” says Dr. Reich. “Studies have demonstrated that both forms of machine perfusion can outperform SCS, providing better preservation, ability to test, treat and repair organs, increased access to transplant, and safer outcomes.”

Cleveland Clinic’s transplant centers in Weston, Florida, and Cleveland, Ohio, have implemented normothermic and hypothermic machine perfusion preservation for certain liver transplants, using the OrganOx Metra normothermic device and the Bridge to Life VitaSmart hypothermic device. Only a few liver transplant programs have experience using both approaches to dynamic preservation.

HOPE versus SCS

Dr. Reich is continuing to add to this body of research as the national lead investigator for the Bridge to HOPE Liver Clinical Trial, which is evaluating the clinical safety and efficacy of SCS compared to cold storage followed by hypothermic oxygenated perfusion (HOPE) with the VitaSmart™ Liver Machine Perfusion System.

Cleveland Clinic’s transplant centers in Florida and Ohio are two of the 15 study sites currently enrolling patients undergoing liver transplantation with DBD and DCD organs. The study launched in December 2021 and is enrolling up to 244 patients over 2 years. Researchers are looking at the rate of early allograft dysfunction between treatment groups, rates of ischemic cholangiopathy, and patient and graft survival post-transplantation.

Dr. Reich presented early results from the multicenter, randomized, controlled trial last November at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases 2022 Meeting. Based on the first 61 enrolled patients, a lower rate of early allograft dysfunction was observed in the HOPE arm (22%) compared to the SCS arm (34%). Patients in the HOPE arm also experienced a shorter median hospital stay post-transplantation than in the SCS group, 9.5 days compared to 11.4 days, respectively. “These and our more recent results are very encouraging and give us great optimism about HOPE,” says Dr. Reich.